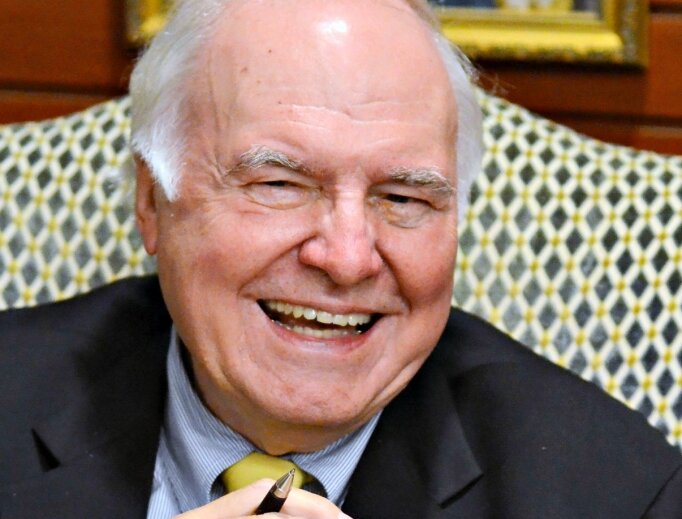

Michael Novak (1933-2017): Large in Life, With an Even Larger Heart

/By Father Raymond J. de Souza

Originally published on February 24, 2017 on National Catholic Register

The news that Michael Novak had died Feb. 17 at age 83 was properly an occasion for celebrating his massively influential scholarship and writing. He lived a large life, and his even larger heart meant that a great many people had a place in it.

There were many who were closer to Michael than I was, as we did not have frequent contact, but perhaps I might offer a few thoughts representing the enormous number of people he touched along the paths of a rich and varied life.

The Family Gathers at a Funeral

While I had read Michael Novak in the late 1980s as a student, I first met him at the famous Kraków summer seminar that he founded, along with Father Richard John Neuhaus, George Weigel and Father Maciej Zieba.

Those weeks we spent together in July 1994 were decisive for my vocation, and not only were Michael’s lectures influential, but so was the time he spent with us in informal conversations. It was a surprise to me that such an esteemed author would want to converse with us, let alone ask us what we thought. Over the subsequent years, a friendship with Michael developed, as with other faculty at the seminar.

In 2009, after the funeral Mass of Father Neuhaus, at which I preached the homily, Michael approached me at the graveside.

“I am so pleased that one of ours was able to preach today,” he said quietly. It was a reminder that it was not only the vast numbers of his intellectual and spiritual children who regarded him as a mentor and father, but that he, too, looked upon what he had built as something akin to a family.

Michael’s long life could be read as an ever-expanding invitation to become part of that “ours,” a circle of friendship, intellectual fellowship and, above all, faith.

On that occasion, as on many others in recent years, the “ours” of which Michael spoke became more evident. The number of scholars, publications, think tanks, institutes, academic programs and students influenced by Novak is immense.

Few theologians can claim to have influenced a papal encyclical with their writings, as Michael did with 1991’s Centesimus Annus, but more impressive was the impact he had outside of the largely clerical world of theology. It is because of the pioneering work of Novak in the 1970s that the world of theology is rather less clerical than it used to be, with laypeople embracing their mission as students and teachers of theology.

It is unremarkable today when laypeople give the leading theological presentations at scholarly gatherings or bishops’ meetings, to say nothing of the theological training of many staff in parishes and schools. Novak was a pioneer. His work in the 1980s in response to the American bishops’ pastoral letter on the economy was subtitled “A Lay Letter,” reflecting both his view that the lay faithful ought to be theologically formed and that theological reflection on the temporal order of work and economics needs their expertise borne of experience.

The family — the “ours” of which Michael was a father, grandfather and godfather — was not, in the end, primarily an academic one, much less a particular school of thought on economic and political liberty. It had a place for all those who thought the great adventure of being Catholic could be fully lived out in everything from starting a business to playing sports to being interested enough to start a conversation.

Notre Dame, Ave Maria, Our Lady and His Lady

Notre Dame football brings together religion and sports in a particularly pleasing way, and so there was no doubt that alumnus Michael Novak would be at the national championship game in January 2013 in Miami. (Notre Dame got thumped by Alabama.)

As a young man, Novak was an aspirant for the Holy Cross Fathers and studied at Notre Dame for many years. The priesthood wasn’t his calling, but theology was. When he began writing about theology and economics in the 1970s, Catholic thinking was often suspicious of economic activity and frequently hostile to free markets.

Novak challenged the regnant view and invited Catholics to think about economics not as grubby grasping after filthy lucre, but as a great arena of human freedom. It is in the economy that man cooperates with others to provide for his needs and those who depend upon him, employing his creativity as one made in the image of God.

Novak’s most important book was published in 1982, The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism — a book so influential that it was passed around by the underground resistance behind the Iron Curtain. He taught us in that book to seek the spark of the divine in the mundane worlds of economics and politics.

In January 2013, though, it was The Joy of Sports that I reread before heading to Florida to cover the championship game. Just as he saw the divine spark of creativity in economic life, he glimpsed it in baseball, basketball, football and various other sports. Readers will find in Novak’s 1976 book why he is not a theologian of economics as much as a theologian of freedom.

“Play is the most human activity,” Novak wrote. “It is the first act of freedom. It is the first origin of law. (Watch even an infant at play, whose first act is marking out the limits, the rules, the roles. … The first free act of the human is to assign the limits within which freedom can be at play.) Play is not tied to necessity, except to the necessity of the human spirit to exercise its freedom, to enjoy something that is not practical, or productive, or required for gaining food or shelter. Play is human intelligence, and intuition, and love of challenge and contest and struggle; it is respect for limits and laws and rules, and high animal spirits, and a lust to develop the art of doing things perfectly.”

After the game, I headed to Ave Maria University, the Catholic university founded by Tom Monaghan, along with the accompanying town, also named Ave Maria. I went to visit Michael, and, though he was disappointed in Notre Dame’s loss, he quickly delighted in showing me around the campus and the town, arranging for me to meet his new friends over dinner. We had gone over to the chapel for Mass, but made a mistake about the schedule, so Michael, despite his difficulty in getting around, set out to find a chaplain, a sacristan, a custodian — whoever might help us. His piety at Mass, which I had witnessed often, was inspiring, if it was on that occasion just the two of us.

He took me to the library, to which he had donated several paintings of his late wife, Karen Laub-Novak. He was immensely proud of them and guided me through until we came upon a portrait of Karen herself, painted when she was much younger.

We sat in front of it, and for more than an hour, Michael told me a great love story, of how he and Karen met, how he persuaded her to marry him, and of the early years of their marriage, which included his time in Rome covering Vatican II. She died in 2009, and he missed her terribly. As he beheld her portrait, he told me, “She looked just like that to the end.”

She did not, of course, for she aged like anyone else, and illness took its toll. But Michael saw her always with the eyes of love. He always saw the beauty that first captured his heart and accompanied him through life.

As Michael’s work matured, love took a more central place. It did not displace freedom, for love is always a free choice, and freedom finds its deepest meaning in love.

He began to write about caritopolis, the City of Love, the social order defined by increasingly broad and deep loves. His love of God, his love of Karen, his love of family and friends, his love of love as what makes man most fully alive — all this came to occupy a more central place in his thinking.

He was fond quoting Dante about God as the “love that moves the sun and the other stars.” Love was the great force of creation. So I was not surprised to read that, for those who were able to visit him in his last days, he said simply: “God loves you, and you must love one another — that is all that matters.”

Singing With a Saint

A year after my participation in the Kraków seminar, a reunion of sorts was held in Rome. On July 26, 1995, our group was invited to Castel Gandolfo for the morning Mass of Pope John Paul II. Michael was immensely proud that the great pope of our times was a Slav, for Novak’s family was from Slovakia.

Some years after he began the Kraków summer seminar, Michael would start another in Slovakia, a gesture of gratitude to his homeland. There was more than ethnic kinship though, for Novak saw in John Paul the great champion of the freedom that he had been advancing, a Christian humanism convinced that, as St. Paul puts it, it is for freedom that Christ has set us free. Michael’s admiration for John Paul was profound, and he never lost his amazement that the Pope would want to speak with him and read his work. I ran across him in Rome in the early 2000s, and he was delighted to relate that he would be going to dinner with John Paul the next day.

“I used to be invited to have dinner with the Pope because I was Michael Novak,” he told me. “Now, I am invited because I am a friend of Mary Ann Glendon. It doesn’t matter, because it means I still get to meet the Pope!” It wasn’t quite true, but Michael was humble enough to rejoice in the blessings that came his way, in particular the singular blessing of St. John Paul II.

Toward the end of the Mass at Castel Gandolfo, there was an extended period of silent prayer after holy Communion. Then John Paul began to sing by himself. It was the Ave Verum Corpus, a hymn both Eucharistic and Marian.

None of the students knew it, and even if we did, it was unlikely that we would have had the courage to join John Paul in singing it. After all, even the Pope’s secretary and the household nuns had not joined in. But Michael did. He was on my right, the Pope just ahead on my left, and he began to sing with the Pope — the two Slavs singing in honor of the Mother of God in gratitude for the gift of the Incarnation. It was immensely moving; Michael’s eyes were moist; I was crying. (St. John Paul seemed fine.) To this day, I can’t hear the Ave Verum without the memories of the chapel at Castel Gandolfo coming back, a young man in the company of two men who would shape my life.

As Michael Novak is mourned by his family and his friends and all those who belong to that great “ours” that radiated out from him, I would like to think that he is with St. John Paul the Great in heaven even now, singing the Ave Verum, but no longer just the two of them, but, instead, that immense multitude around the throne, beholding the Love that moves the sun and other stars.