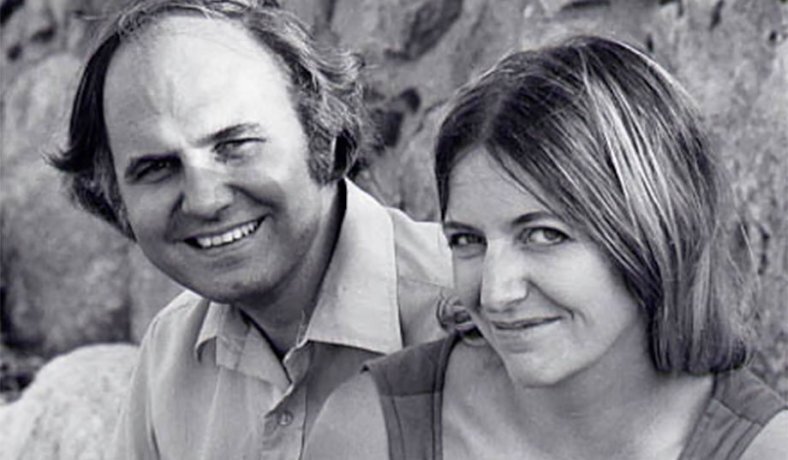

Michael Novak and Karen Laub: A Love Story

/By Mary Eberstadt

Originally published on February 24, 2017 on National Review

Michael and Karen (Photo courtesy of Jana Miller)

The private writings of a wonderful couple.

Editor’s note: The following are excerpts from a dinner speech given by Mary Eberstadt on the occasion of Michael Novak’s 80th birthday at Ave Maria University, September 21, 2013.

Michael Novak has now turned 80 — and what a privilege to have been present here and in Washington as so many have sounded his praises this week. We’ve heard from family members Ben, Jana, Mary Ann, and Rich; from editors, authors, philanthropists, and diplomats; from at least one Supreme Court justice – and from a standup comedian who moonlights as a constitutional-law professor named Hadley Arkes. To that list we can also add the wonderful speeches by Father Derek Cross, Samuel Gregg, Michael Pakaluk, Brian Anderson, David Dalin, and George Weigel, during the conference earlier this morning.

Tonight I’ll try to add something different to that distinguished heap. I’ve been asked to talk not about his brilliant career, but instead about personal recollections of Michael and Karen Laub Novak, his late wife.

By way of credentials, I’ve known Michael and Karen since the mid 1980s, when he helped to open the door to the American Enterprise Institute for my then-future husband, Nick. We four became fast friends, Michael and I perhaps fastest of all — probably because one of the first things I uttered to him was a compliment on his then-long white hair. Michael is also known to us, as to everyone present here, as an unfailing friend and a generous mentor who goes out of his way to read, write about, and encourage diverse work by many others; to endorse books and make connections; and otherwise to bring unexpected joy into the lives of others, including unsung joy. Karen was a cherished, terribly missed friend (some of my memories of her appear in a piece published in First Things in 2009).

Our subject tonight is dearer to Michael than any other, and that is their life together. It’s been my privilege to have a window on that world, including lately via documents that almost no one else has read: a collection of their love letters dating from the early 1960s, shared by Michael as he ruminates on whether they might someday see print. I’m here tonight to meditate a little on some of what those letters show.

The correspondence covers a period of months beginning with their meeting on a blind date on March 22, 1962. During that time, the two are mostly separated, reporting to one other with local color from Iowa and Cambridge, Mass., Paris and Rome, and points in between. The plot, setting, and characters are as absorbing as good fiction. As Michael observes at the opening, “the written record tells this love story better than a novel would, or even a biography.”

These letters are extraordinary because they are, first, an extended and invigorating journey into the young lives and minds of two uniquely gifted people. One of our protagonists is Karen Laub, later to become Karen Laub Novak — a 24-year-old artist of serious mien, former student of Oskar Kokoschka in Austria, already making her own artistic mark on the world. Intriguing, at times conflicted, she is the more taciturn of the two — a shy beauty from wholesome Iowa, drawn artistically and intellectually to the soulful and difficult aesthetic matter made manifest in her later work.

Her favorite book is St. John of the Cross’s Dark Night of the Soul. So is his. What are the odds of that?

Michael decides immediately upon meeting that he wants to marry her; and from that moment, the chase is on. He’s a novelist, student, and scholar, already publishing and traveling widely when these two meet. In these letters, we see a side that has not been revealed before: an ardent young man in heady, sometimes even ferocious, epistolary pursuit. By turns playful and serious, his letters are both compelling in themselves and instructive for what they reveal of the energy, discipline, and wide range of interests that have been essential to his public life.

The correspondence is also striking in another way. This is one of the last collections of love letters written in our lifetimes that anyone examining it will ever read. It’s poignant but true: Almost no one under middle age today will ever know letters as lovers before them knew those things: the heart-stopping sight of familiar stamped stationery in the mailbox; the trembling hands upon opening the envelope; the unbidden impulse to smell deeply of the paper; the thrill of seeing a missive signed “love” for the first time – or the churn of the stomach upon realizing that it is not. People will no longer know these things because people today no longer write such things — not 24-year-old artists nor 28-year-old authors nor anyone else.

None of which is to say that romance is anything other than the confounding tragicomic spectacle it always has been; only that today, and maybe even forever, it finds electronic rather than paper pathways. Texting and tweeting and e-mailing and sexting all get the job done, breaking or binding hearts in the ether; after all, something has to. But the sustained exercise of the paper form they’ve replaced was and always will be singular, the more so as it recedes into time.

“Letters were first invented for consoling such solitary wretches as myself.” So wrote Héloïse to Abelard, and she should know. In that same missive from almost a thousand years ago, Héloïse also expresses perfectly what the writers of love letters have shared across millennia: “Having lost the substantial pleasures of seeing and possessing you, I shall in some measure compensate this loss by the satisfaction I shall find in your writing. There I shall read your most sacred thoughts; I shall carry them always about with me, I shall kiss them every moment. . . . I cannot live if you will not tell me that you still love me.”

Related thoughts pepper the letters of Michael and Karen. As a portrait of the artist as a young man, Michael’s letters leap with energy. The months he spends in Europe, all the while writing Karen of his experiences, make for especially vivid reading. His pages brim with references to plays, operas, travel, salons, dinners, and other engagements. He zooms through the streets of Rome and Paris, absorbing and reflecting as only the young and ambitious can — smells, food, language, history, architecture and art, people. All these he imbibes fully . . . the better to transmit to Karen in the next letter.

As for his studies, it may hearten some to know that the world-beating theologian complains often in these letters of the subject he dreaded most: Symbolic Logic.

Our ambitious young man strives to find the same success with the object of affection that he does with his work – only to betray frustration that women are, after all, more intractable than books. Declaring, joking, begging, conjecturing, exclaiming: There is nothing Michael won’t do to get a letter out of Karen Laub. “Write when you can, even if it burdens the U.S. mails and all of Europe terribly,” he signs off on his departure for Rome. “Think of me in a prayer (other times are ok, too),” he clarifies elsewhere. Less oblique: “In your good time, do miss me & hurry up & fall in love!”

This brings us to one more theme that lifts their story out of the realm of private life and into the world we know: its portrayal of the struggle of an ambitious young woman over two goods often at odds with each other — the solitude needed for artistic creation, and the nonstop white noise of domestic life. Too gifted to be Everywoman, the young Karen nevertheless wrangles with large matters immediately recognizable to all young women today – the tension between wanting to give all to her art and knowing that life with husband and family will complicate all that forever.

One final thread connects youthful romance here to something lasting. That is the presence in these pages of love as defined by Thomas Aquinas: willing the good of another. From the beginning of their time together, these protagonists share a mutual dedication toward one another’s work and well-being.

They bequeathed gifts artistic and intellectual, separately and together, for decades.

From early on, Michael urges Karen to try for a Guggenheim or Prix de Rome prize, and to mount showings of her work. He learns about art for her sake; he coaches and fills her in about his writing. “You’ve got to learn how much pleasure your work will bring to people and how deep your talent runs,” he tells her. Karen repays the interest, consoling him over disappointment about book sales, and otherwise sending thoughts on his work. “It would be such fun if you would write a few short things (poetry or stories) sometime and I could illustrate, set the type and print it,” she suggests in the first months.

It’s an impulse to collaboration that foreshadows what will become their longest-running orchestration of all, a marriage of 46 years.

In the end, the story of Michael and Karen also reminds that the command to be fruitful and multiply has more than just a literal meaning. With these letters, what began as their offerings to one another fuse to become the ground from which they’ll bequeath gifts artistic and intellectual, separately and together, for decades to come – to family and friends all over, and to beneficiaries of their many creations around the world. “It really takes a great deal of work on both sides to create something beautiful,” the twenty-something Karen observes. And they did.